INTRODUCTION

During the 1860s, my young grandfather, James Renn, along with his parents and siblings, fled the Agricultural Depression in western Ireland for booming Chicago. They survived the Great Fire of 1871 and, as Chicago forged ahead, so did they. Personal tragedy struck the family in 1879 when my great-grandfather died suddenly. In the following years, his widow, Mary Ellen, and her seven children recovered, not only surviving, but prospering. By the 1890s, the family had secured its future, both financially and socially, as entrepreneurs, property owners, teachers, and medical doctor. How did the family find the means to launch itself solidly into the middle class? A mysterious windfall? I wonder. Work, opportunity, and savvy dealings? I have no doubt.

A NEW LIFE IN CHICAGO

Waves of Irish immigrants arrived in the United States during the 19th century. My great-grandparents and five of their children rode one of those waves in the late 1860s. The family was from the west country, County Mayo and County Leitrim, where most of the rural people were small tenant farmers and agricultural laborers who survived by working off-season as stone-breakers or road-workers. An agricultural depression hit farmers in the west of Ireland hard, a breaking-point for many who had survived the Irish Potato Famine of the late 1840s and early 1850s.1 My mother’s paternal grandparents, James and Mary Ellen MacCrann left Ireland about 1869 for Chicago, where explosive growth offered opportunity – but Chicago was not without its own perils.

In Chicago, my great-grandfather, now using the surname Rinn or Renn, worked as a laborer, according to City Directory listings. Chicago was expanding; its population grew from 112,172 in 1860 to 503,185 in 1880.2 Its hunger for roads, houses, factories, and warehouses was voracious. It was easy to find work, but unskilled labor, as in Ireland, did not lift a family out of poverty.

James and Mary Ellen’s eldest son, Patrick, was 13 when the family arrived. There were no child labor or compulsory education laws in Chicago at the time. He and his sisters Bridget, age 9, and Ellen, age 6, may have attended the Catholic parish school, but Patrick certainly worked to help support the family, which included four younger children: James, 5; Marie, 4; and two infants, Catherine and John.

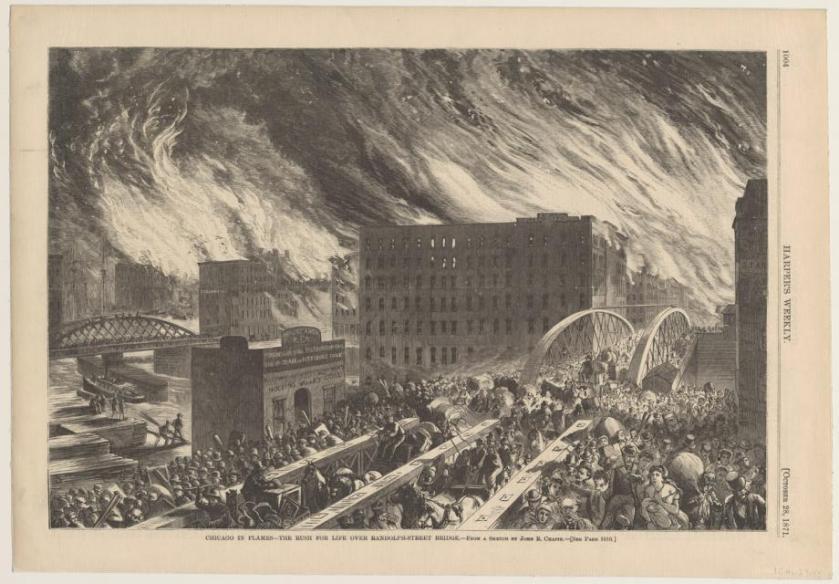

FLEEING DANGER: THE GREAT CHICAGO FIRE

The family’s first footholds in Chicago were threatened, along with their lives, in the early hours of Monday, October 9, 1871. Chicago’s Great Fire started at the far end of the city, the southwest side, at 8:30 pm on Sunday, October 8, but quickly advanced northward. It jumped the main branch of the Chicago River at 1:30 am on Monday and roared unimpeded through the North Division, where the Rinn family lived. The fire burned everything east and south of the family home at 363 E. Division Street, and perhaps their home, too, before rain stopped it late on October 9th.

The terror and loss experienced by the Rinn family was shared by their Near North Side neighbors. Immaculate Conception parish was the center of life for the Irish Catholic families. The parish school was established in 1868 by Sinsinawa Dominican sisters who recorded their experiences during the fire. The sisters fled, along with church parishioners, to the west along Division Street to Goose Island. They carried what they could and buried the rest – including their piano!3 My seven-year-old grandfather and his family may have joined the nuns in their flight.

The Sinsinawa religious community immediately sent hundreds of dollars to help parish families and to rebuild Immaculate Conception church and school. The example of the spirited and devoted nuns must have made a big impression on my great-aunts Bridget and Ellen, as they both joined the order in the following decade.

As the fire threatened, the family’s fears were heightened by concern for infant Thomas, born 19 days earlier. Thomas survived, but ten months after the fire, three-year-old Catherine died. I don’t know where the family lived after the fire or the circumstances of Catherine’s death, but certainly it was a tragic time for the Rinn family. Within a few years, however, family life stabilized. They lived in the rear of 387 Division Street, a few doors from their residence at the time of the fire. Patrick worked as a plumber and, with two full-time wager-earners, once again the family moved forward.

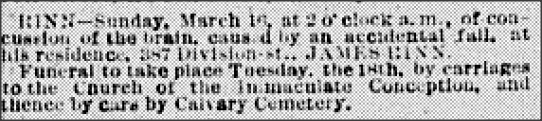

Death of the Patriarch

It wasn’t long before the family again encountered crisis and death. In 1879 my great-grandfather fell down the stairs at home and died of a concussion at 2 am on Sunday, March 16. He was 53 years old. Mary Ellen and her children were bereft of husband and father, but not without resources. Although my great-grandfather had no known siblings, his widow Mary Ellen, née Reynolds, had three brothers and one sister living in Chicago and the extended family was close. A neighbor who lived at the same address as the Rinn family, John McHugh, had contracts with the city to install sewer pipes and may have helped the brothers Patrick and James establish their own contracting business.4

After the death of my great-grandfather, the surname Rinn was not used again. In earlier Chicago records, the spellings Renn and Wren are occasionally seen, but henceforth city directory listings, marriage, death, census, property, and business records were all in the name of Renn. The last surviving record in the name of Rinn is the obituary for my great-grandfather.

Over the next five years, life changed dramatically for the Renn family – for the better. By 1885 they were living in a multi-flat building that they owned at 227 Townsend Street. The two eldest daughters Bridget and Ellen had both taken orders with the Sinsinawa Dominicans and were teaching in Catholic elementary schools. James, my grandfather, had joined his elder brother Patrick in the plumbing trade, as would John soon after. Two years later, in 1887, 17-year-old Thomas was studying at a business college in downtown Chicago and would soon enter medical school. Widow Mary Ellen and her youngest daughter Marie kept house.

Patrick, James, and John , ages 29, 21, and 16 respectively, were all working as plumbers, but their earnings alone don’t account for the capital needed to purchase property and send their younger brother to medical school. How can this apparent influx of money be explained? During divorce proceedings in 1896, Thomas Renn’s wife sought a share of what she claimed was valuable property owned by her husband and his siblings. Thomas Renn’s lawyer disputed that Thomas had a share in the property from “his parents’ estate.” Rather, he had received a cash advance used “in his literary and medical education.”

The source of the assets that, in the 1880s, propelled the Renn siblings into the comfortable middle class remains a mystery. Whatever the source, Patrick, James, Marie, John, and Thomas Renn banded together to attain and protect financial success. Regular newspaper notices of contracts awarded by the city between 1900 and the 1920s attest to the business success of my grandfather James and his elder brother, Patrick. As does the published account of the marriage of my grandfather, then age 26, to Brigid Connelly. The report reads, in part,

The bride wore a dainty gown of white mulle over taffeta with garniture of valenciennes lace. Her tulle veil was fastened with a gold star studded with rubies, the gift of the groom. October, 1900, source unknown.

The gold star studded with rubies vanished from the family, as did the prosperity. After the death of my grandfather in 1926, an extended lawsuit between my grandmother and Patrick Renn was continued after Patrick’s death by his sister Marie and not settled until 1932. In the meantime, the Great Depression destroyed the value and rental income of the real estate in dispute.

My mother was a teenager during this turbulent period and the memories that she passed on to her children were those of loss. Her father died in 1926 on the same day as her maternal grandmother. The family lost their home. Brigid Renn, in her mid-fifties, went back to school for her teachers certification and then worked to pay the bills. The only surviving adult male in the family, my mother’s brother, John, died in 1934 at age 32. Shortly thereafter, Brigid Renn filed for bankruptcy to save what little was left.

The Renn family saga did not end with bankruptcy. The legacy of perseverance and family bonds- and the good fortune that is always an essential part of success – was passed on. Middle-class prosperity was once again attained by the family. My parents, Helena Renn and Roland Johnson, made sure that I and my siblings grew up with hard-won financial security, a solid education, and a life embedded in extended family, community, and church. That, however, is a story for another day.

References

- Donald E. Jordan, Land and Popular Politics in Ireland: County Mayo from the Plantation to the Land War (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 145.

↩︎ - James R. Grossman, Ann Durkin Keating, and Janice L. Reiff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Chicago (University of Chicago Press, 2004), 233.

↩︎ - Mary Synon, Mother Emily of Sinsinawa: American Pioneer (The Bruce Publishing Company, 1955), 125-126.

↩︎ - Obituary, John McHugh, Chicago Tribune, 22 Dec 1890, 2. ↩︎

Leave a comment