Today, as I start my writing, it is the 100th anniversary of Armistice Day, November 11, 1918, that ended World War I. Until recently, I didn’t know much about the war other than its major hits: the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the network of alliances that led one European country after another to fall into war, the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, and the move from neutrality to war by the United States in 1917.

There were family members who served in World War I, but I didn’t know that growing up. My mom was just five years old in 1917 and my father was an infant. I’m not sure that either of them ever thought much about World War I, which was eclipsed in their lives by the Great Depression and World War 2. But there was a secret, born within World War I, at the heart of my childhood family life: the Spanish flu pandemic of 1818-1819, which orphaned my father and his four siblings in Sweden. Soon after, my father was taken in by the Johnson family who themselves had lost their only son to the flu in December 1818.

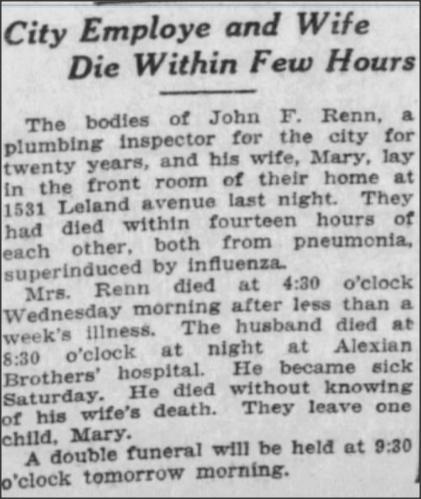

The Spanish Flu killed 50 million people around the world, perhaps up to 100 million. In contrast, World War I directly killed about 16 million people. But the deaths of war and disease were entwined. The flu spread rapidly across the globe by the movement of troops during World War I and the death toll was so heavy, in part, because of the poor nutrition and crowded conditions caused by the war. The flu killed quickly and young adults were the most likely to die. In Sweden, my father’s young parents both died on April 29, 1919. In Chicago, my grandfather’s brother John Francis Renn and his wife Mary both died on January 22, 1919. Their 16-year-old daughter Fabian also fell ill, but survived.

In April 1919, my father Roland and his twin Olaf were nearing two years old. Their three older siblings Tage, Ragnar, and Sonja were 9, 8, and 6 respectively. The five children were living in the city of Örebro in central Sweden with their mother, Lydia Emilia, age 29 and father, Ivar Leander, age 30. After the death of Ivar and Lydia on April 29, Lydia’s unmarried younger sister, Ida Karolina, stayed with the children while the husband of Lydia’s eldest sister, Karl Nilsson, assigned responsibility by the courts, looked for homes for the children.

Two weeks later, on May 15, 1919, my father was taken in by Carl and Josefina Johnson. Little Roland went from his home in the city with his parents, three older siblings, and twin brother to a rural hamlet where he lived with an older couple, Karl and Josefina Johnson and their 22 year old daughter Florence. All five of the orphans eventually found their way in the world, married, and, with the exception of Ragnar, had children and lived to the 1970s or beyond. The three living siblings, Sonja, Olaf, and Roland were reunited in 1977 in Sweden.

It was only then, in 1977, in my mid-twenties, that I learned any of this. I hadn’t known my father was adopted, or that he was born in Sweden. I hadn’t known he had four birth siblings, including a twin brother. My father’s speech patterns, so familiar but never recognized for the accent it was, came clearly into focus. So too the clipped answers and sense of unease when I brought home forms from school asking for my parents’ places of birth. Secrecy about my dad’s birth in Sweden and his adoption hung over us kids, but also a drive and discipline fueled, in part, by my father’s immigrant experiences. When we were young, we may not have understood the source of my father’s fierce pursuit of respectability and security, but we did benefit from it. To my father, I was “Bet” not “Beth.” Now I know better the origins of Bet.

Leave a reply to Alex Cochrane Cancel reply