The 20th century did not have a lock on independent women in my family. In the 19th century, teaching was a path to independence, a path taken by five of my female ancestors, three of them as Dominican Sisters of Sinsinawa. I want to share what I know about the work of these three sisters and the contribution of their religious community to the immigrant and pioneer families who settled in the prairie states.

The congregation of Dominican sisters at Sinsinawa, Wisconsin, was founded in 1847 by the missionary priest Father Samuel Mazzuchelli, O.P. (Order of the Preachers), with Sisters Seraphina and Ermeline. After Father Samuel’s death in 1864, a young Emily Power was elected Prioress of the congregation. Known as Mother Emily, she led the sisters through a transitional crisis and embarked them on an expansive mission of establishing schools in frontier towns and cities in Wisconsin, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, and Nebraska. Throughout, Mother Emily kept her focus on justice and charity. The last mission school that she authorized, in 1907, was St. Peter in Anaconda, Montana, a growing copper smelting town with a large population of immigrants and laborers.1

Mother Emily was an extraordinary woman with a progressive vision. She developed a liberal arts curriculum for the sisters in her care as well as for young women in farming and urban immigrant communities. Scholarship and learning are the foundation of the Dominican order and Mother Emily democratized opportunities to engage in rigorous study and inquiry. Mother Emily was one of the first Superiors in the United States to send sisters to study in secular institutions such as University of Chicago; Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois; Washington University in St. Louis, University of Wisconsin in Madison; Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C; and abroad. Mother Emily was also active in social movements addressing poverty and workers’ rights. For example, she sent aid to striking and locked-out miners in Spring Valley, Minnesota; Anaconda, Montana; and the stockyards of Chicago.2 Mother Emily and her congregation of sisters were dedicated and daring innovators in both education and social action.

One of the schools founded under Mother Emily’s leadership was the parish school at Immaculate Conception in Chicago, the first Catholic church built north of the Chicago River for English-speakers (i.e. Irish immigrants). My great-aunts Bridget and Ellen Renn likely attended school at Immaculate Conception and were taught by the Sinsinawa Dominican sisters. Inspired by their teachers and their own faith, Bridget and Ellen Renn both joined the order, in 1877 and 1885, respectively.

I wonder what opportunities my great aunts had under Mother Emily’s tutelage. Were they among the sisters sent to the Columbian Exposition in Chicago with orders to learn all that they could? And perhaps beyond, as Mother Emily also sent sisters to study in New York and Denver, even Europe. The liberal arts education, including the sciences, received by the young women must have been exhilarating, but their training also prepared them to live difficult and rigorous lives pursuing the mission of “economic philosophy and social justice” that Mother Emily learned from Father Mazzuchelli and passionately passed on to her congregation.

My great-aunt Ellen Renn took the name of Sister Cecilia when she took her vows. Her talents and commitment were surely recognized early, as she was given a series of increasing difficult assignments. Early on, Sister Cecilia served as Convent Superior in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Later, she moved to Omaha, Nebraska, and lived at Sacred Heart Convent while working across town at St. Cecilia’s. According to her congregation obituary, Sister Cecilia “endured many hardships going across the city and working under pioneer conditions at Saint Cecilia’s.” When the convent at St. Cecilia’s Cathedral School was finally completed, Sister Cecilia was the Convent Superior. Her peers reported that during her time in Omaha, Sister Cecilia “was always earnest and cheerful and willing to make sacrifices for the common good.”

An urgent plea in 1920 sent Sister Cecilia to Imogene in the southwestern corner of Iowa. Father Edmund Hayes, head of St. Patrick parish in Imogene, requested aid after the departure of the Sisters of Mercy, who had irreconcilable disagreements with the opinionated Reverend Hayes. Father Hayes was a noted orator and world traveler, described by his contemporaries as “the best known Catholic priest in Iowa” and also “one of Iowa’s richest men.”3 He had strong ideas about his parish, and his money amplified the power that accrues to a pastor. He drew on his personal fortune to build an English Gothic style church with a Carrara marble high altar and stained glass windows from Italy. The church cost $125,000 in 1919 dollars; equivalent to over $1.9 million dollars today, half of which was paid for personally by Rev. Hayes.4

The delegation of four sisters sent by Mother Emily to Imogene was led by my great-aunt Sister Cecilia, who took on the role of principal of St. Patrick’s Academy. In her Sinsinawa obituary, Sister Cecilia is lauded for “cooperating with an eccentric pastor, the Reverend Edmund Hayes, whose ideas of school management were difficult to interpret in the modern school.” When Reverend Hayes died in 1928, he left the Sinsinawa congregation $10,000 (about $166,000 today) in appreciation of the efforts of Sister Cecilia.

Sister Cecilia spent two years working as a librarian at Visitation High School in Chicago before she died at age 77. Her requiem mass was attended by Monsignor Daniel Byrnes, 20 priests, and the entire student body of Visitation High School. Monsignor Byrnes accompanied the remains of Sister Cecilia on the train to Saint Clara Convent at Sinsinawa for a second requiem mass. In her congregation obituary, Sister Cecilia was remembered as having “a cheerful and kindly disposition.” Her many accomplishments suggest that she also had a bold and determined spirit.

Sister Cecilia’s older sister, Bridget, assumed the name Sister Fabian when she took her vows in 1877. Sister Fabian’s congregation obituary notes that she “spent many happy years” at Edgewood Villa on the shore of Lake Wingra in Madison, Wisconsin. In 1881, the Villa and surrounding 55 wooded acres on the shore were gifted to the Sinsinawa Dominicans by Wisconsin’s Governor Cadwallader Washburn. It was at Edgewood, in 1903, that Sister Fabian developed the pneumonia that led to her early death in 1903. Her obituary describes her as having a gentle nature suited to her work as a teacher and prefect of younger girls.

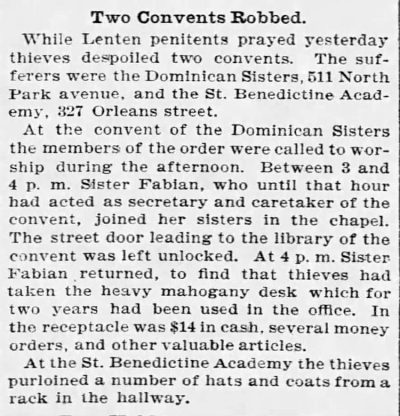

It is likely that Sister Fabian was assigned to schools in addition to Edgewood. In fact, there is a 1902 Chicago Tribune news story about a Dominican convent burglary at 511 North Park Avenue that features Sister Fabian, although it’s not impossible that there were two Dominican sisters named Fabian at that time. The story adds some color to what we know of how the sisters lived. The article reports that Sister Fabian, secretary and caretaker of the convent, discovered a theft that occurred while the sisters were at their afternoon devotions: Sister Fabian’s desk and its contents gone; the front door of the convent ajar; and, subsequently, Sister Fabian relieved of her duties as convent caretaker. This story illustrates that the sisters were very much a part of the world, experiencing its challenges while working to remedy its wrongs.

My third ancestor who joined the Sinsinawa Dominicans was one generation younger than my two great-aunts. Catherine Healy, known in the family as “Kittie,” was my mother’s first cousin. Born in Chicago in 1870, Kittie took her vows in 1894 along with the name of Sister Cecile. After two years of college training as a music teacher, mission assignments sent her to Jackson, Nebraska; Plattsmouth, Nebraska; St. Dominic’s in Minneapolis, and Kansas City, Missouri. By the time of the 1910 census, Sister Cecile was teaching music at St. Clara’s Academy at Sinsinawa Mound. Over the next four decades, she taught music at St. Jarlath’s, Immaculate Conception, and Visitation parishes in Chicago, and another three years teaching at St. Clara’s. She died in December 1955 at St. Dominic Villa, a nursing home at Sinsinawa Mound, at age 85.

Researching the lives of women in the late 19th and early 20th century is difficult due to name changes and because their lives were not recorded in public documents as systematically as the lives of men. I am grateful to the author Mary Synon, who documented the life and work of Mother Emily along with many of the parish schools that the Sinsinawa Dominicans founded. I also appreciate the local historians of St. Patrick’s parish in Imogene, Iowa, who identify by name the four Sinsinawa Dominican Sisters who arrived in Imogene in 1920. That is so rare! In the book Mother Emily of Sinsinawa, Mary Synon describes the many requests received for Sisters to be sent to schools, yet their valuable contributions were rarely acknowledged in historical records. The mission schools of the Sinsinawa Dominicans were usually in struggling parishes with congregations of poor people, and conditions were hard. Many of the Sinsinawa Dominican sisters taught in communities burdened with poverty, poor housing, family problems, crime, and labor struggles.5 Because of the high standards of education and teacher training, the Sinsinawa Dominican sisters were in great demand. Yet the role they played in establishing schools and lifting up young people, especially girls, has remained in the shadows.

The work of my great-aunts Bridget and Ellen Renn and my cousin Kittie Healy is not recorded in awards or plaques, nor in newspaper articles or public obituaries. Their legacy is seen in the steady progress made by girls and women and by the Catholic immigrants who fled harsh conditions in Ireland, Germany, and Italy. Within my family, the memory of them was lost. It has been a privilege to gather together the information preserved by the Sinsinawa Dominican order, by author Mary Synon, and the local historians of St. Peter’s in Imogene, Iowa, and to be able to share it here.

The working lives of my women religious ancestors were, for the most part, unacknowledged, as were those of the approximately 50,000 Catholic women religious in the United States around 1900.6 Contrary to stereotypes, young women did not join religious orders to withdraw from the world; rather, they enlisted in a very public struggle to improve living conditions during the turbulent late 19th and early 20th centuries. Strengthened by their community life and without the demands of marriage and motherhood, they applied themselves vigorously to establishing institutions and practicing their teaching and nursing professions in rugged and at times hostile environments.7

The legacy of the Sinsinawa Dominican sisters manifests itself in families of today who benefit from the progressive education and labor standards fought for and won in earlier centuries. Under the tutelage of Mother Emily, my ancestors Bridget Renn, Ellen Renn, and Kittie Healy received a liberal arts education and teacher training that prepared them to succeed in their mission of equipping young people to rise in life. I am grateful to my great-aunts and to their Sinsinawa Dominican order for the legacy of their work and for their inspiring examples of achievement.

References

- Mary Synon, Mother Emily of Sinsinawa: American Pioneer (The Bruce Publishing Company, 1955), 251. ↩︎

- M. E. McCarty, The Sinsinawa Dominicans: Outlines of Twentieth Century Development, 1901–1949 (Sinsinawa, Wis. 1952), cited on encyclopedia.com, downloaded from https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/power-emily-mother on 5/4/2023. ↩︎

- “Father Hayes Funeral Rites to be Tuesday,” Des Moines Register, February 10, 1928, 4. ↩︎

- “Father Edmund Hayes Dies in Omaha Hospital,” Malvern Leader, February 16, 1928, downloaded from https://malvern.advantage-preservation.com/. ↩︎

- Synon, Mother Emily of Sinsinawa, 188-189, 246-247. ↩︎

- “Catholic Sisters and Nuns in the United States,” Wikimedia Foundation, last modified March 16, 2023, accessed May 11, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catholic_sisters_and_nuns_in_the_United_States. ↩︎

- Carol K. Coburn and Martha Smith, Spirited Lives: How Nuns Shaped Catholic Culture and American Life, 1836-1920 (The University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 221-223. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Beth Johnson Cancel reply